Emre Gurgen

Why this Press Kit?

This Author Press Kit is a collection of promotional materials that offers detailed information on Emre Gurgen, the author of the Ayn Rand Analyzed series. It is designed to make it easy for media professionals to write articles, conduct interviews, and feature my book(s) in their various publications. By providing all the necessary information—about me and my books in one place—this author media kit is designed to increase my visibility, save time, and deliver my book’s details to potential interviewers, journalists, librarians, bloggers, podcasters, influencers, and book sellers. Ultimately, making it easier for these media professionals to write articles, create social posts, develop interview questions, order and stock my books, and prepare to spotlight my books and person on their podcasts, radio shows, TV programs, and blogs. Basically, this press kit is designed to streamline the pitching process for Emre Gurgen and his books. By showcasing, in one convenient digital package, the author’s achievements, awards, merits, and past coverage.

Website & Social Media

Author Website: www.aynrandanalyzed.com

Facebook Fan Page: https://www.facebook.com/referenceguides

Social Proof (Media)

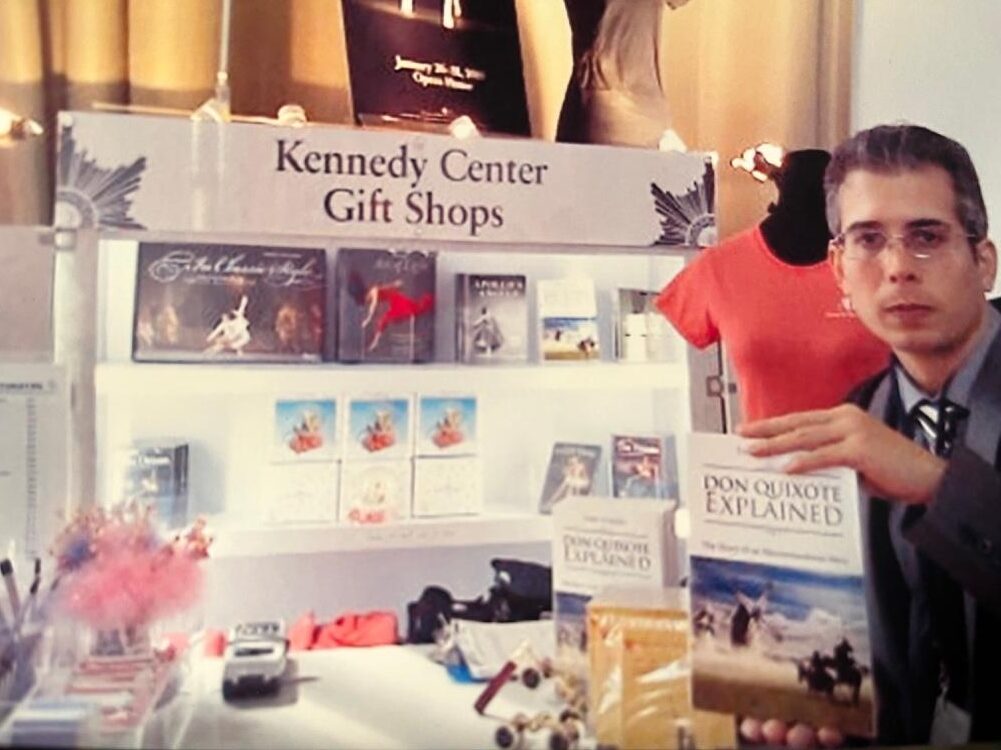

Sold Don Quixote Explained at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts(Washington, D.C.) April, 2014.

Don Quixote Explained selling at a Kennedy Center gift kiosk (Outside of a Don Quixote Opera)

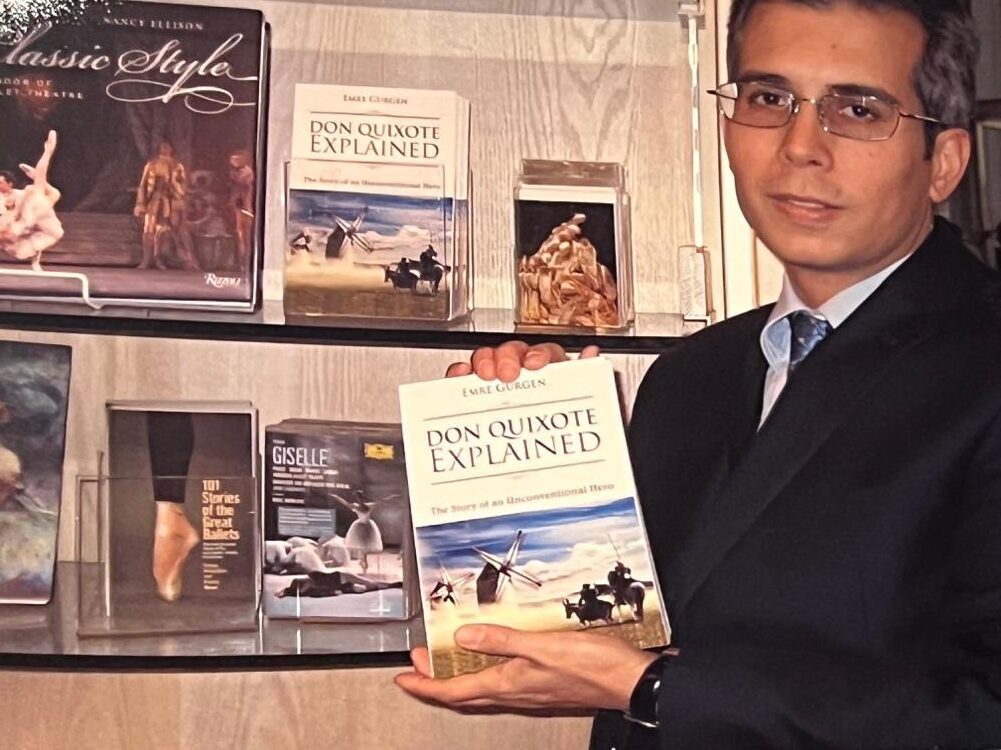

Don Quixote Explained Selling at the Kennedy Center’s Main Gift Shop

5 Star Amazon Review (Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s the Fountainhead)

"Well-written, extremely well-researched, scholarly collection of essays on what the author calls 'the greatest American novel ever written'. I tend to agree. This book is thoughtful, searching, and a pleasure to read. And it enhances one's enjoyment of the classic 1943 novel itself."

* Verified Amazon Purchase

Publications (Overview)

-

- “We the Living” Reference Guide (2026);

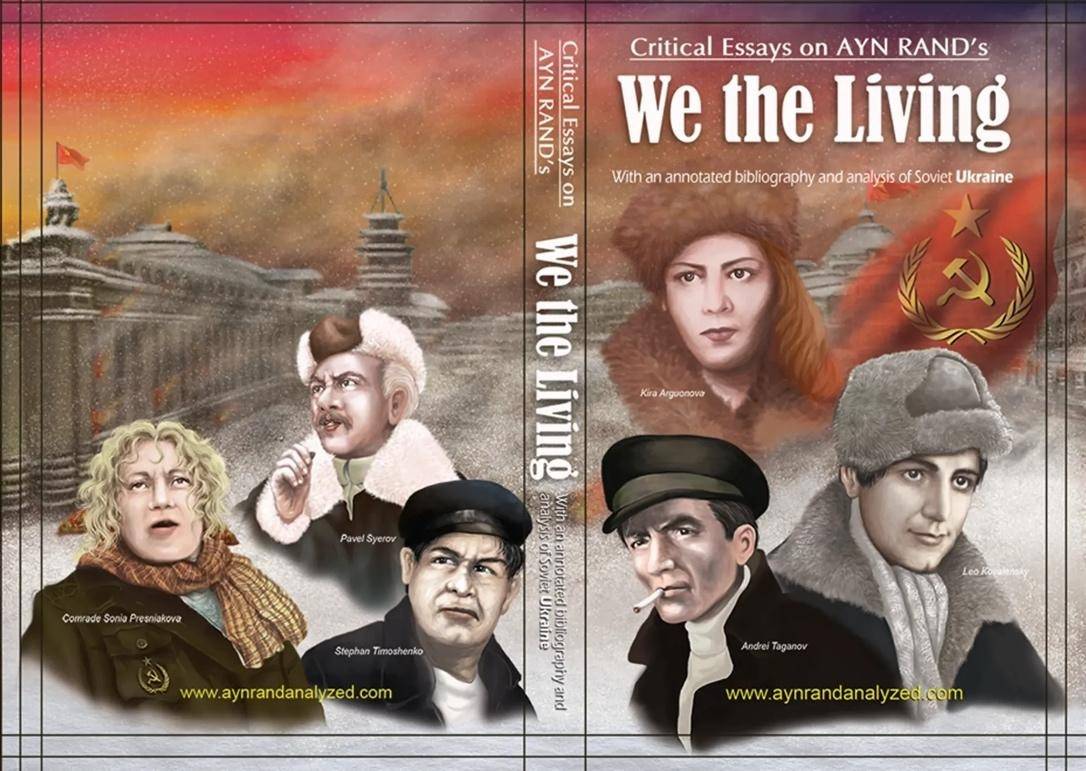

- Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s “We the Living” (2025);

- Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead” (2022);

- “The Fountainhead” Reference Guide: A to Z (2021);

- “The Fountainhead” Reference Guide: A to Z (Brief Version) (2019);

- “Don Quixote” Explained: The Story of an Unconventional Hero 2nd edition (2015);

- “Don Quixote” Explained Reference Guide (2014);

- “Don Quixote” Explained: The Story of an Unconventional Hero (2013).

Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s We the Living

Tagline: “The truth about Soviet Communism.”

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: 12/22/2025

Page Count: 512

ISBN #’s:

- ISBN: 979-8-8230-4911-5 (Hardcover)

- ISBN: 979-8-8230-4910-8 (Softcover)

- ISBN: 979-8-8230-4909-2 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: ($9.99 E-Book; $30.99 Softcover; $50.99 Hardcover)

Purchase Links

Synopsis (General):

Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s We the Living by Emre Gurgen, shows readers, in human-and-particular terms, how Communism degrades the lives of middle-class characters, living in Saint Petersburg, Russia in the 1920’s.

It does this by analyzing how characters are forced to engage in hypocritical, after-hours, social activities, where they must donate their free labor to the State as a socialist duty (otherwise they are fired); how characters, like Kira and Leo, are subject to the jurisdiction of revolutionary people’s courts of class justice, not objective justice, as shown when the State illegally moves a tenant named Marina Lavrova into their apartment. Additionally, Gurgen’s book also examines how characters, like Andrei Taganov, suffer party purges; how other characters, like Sasha and Irina, are condemned to the vast gulag system; how people routinely spy on each other in order to trade information to the state for some kind of reward; how the novel’s Soviet government nationalizes character’s businesses, seizes character’s bank accounts, and breaks into and empties character’s safety deposit boxes; how the book’s socialist State makes Russians queue-up in endless bread-lines for rotten food that is always in short supply; how the book’s centralized State deprives people of their privacy rights, even in their own homes; and, lastly, how the story’s Marxists make characters, like Vava Milovskaia and Sonia Presniakova, raise their children in state-run day nurseries – like the Young Pioneers – since, the family is an institution of the past, according to the book’s many Marxists.

Also, by forcing people to eat meagre amounts of barely edible food, which they have to wait in endless breadlines for, Gurgen’s book shows readers how the Soviet regime damages characters’ health. By not only providing scanty food but also by making people wait outdoors for long periods of time, during which time they are exposed to harsh Petrograd weather, including strong winds, freezing ice, blinding snow, cold sleet, driven rain, and large hail. Weather that causes Petrograd residents to contract frostbite, open sores, respiratory infections, joint pain, dry skin, sore throats, colds, and flues. Weather that exacerbates a character's pre-existing medical conditions, like high blood pressure, diabetes, and vascular diseases, thereby turning non-fatal medical conditions into life-threatening health emergencies. As Russians queue up for hours in all-weather winter conditions, waiting for their meagre rations.

Similarly, Gurgen’s book shows readers that by failing to provide the necessary food for people to function normally, the Soviets abysmally fail in the basic enterprise of feeding people. Since, before the revolution, people shopped for food in grocery stores. But after the revolution, all large social supplies and provisions—like food, housing, medical care, and higher education—are centralized and distributed by state agencies, governmental co-operatives, trade unions, and communal kitchens. Until the former middle class (bourgeoisie) can only get these supplies by either working for the Soviet government, or being trade union members, or both. A prospect impossible to many middle-class characters, since most characters with a questionable social past are banned from working for the government. Because, once upon a time, they were factory owners and tradesmen, not from the work bench or the plough, but rather from a high-class background. So, now, they are subject to a food dictatorship, where characters have to fight for access to a shrunken pool of goods frugally doled out by severe authorities.

Besides examining these topics, Gurgen’s book also scrutinizes how characters are forced to engage in hypocritical, after-hours, social activities, where they must donate their free labor to the State as a socialist duty (otherwise they are fired); how characters, like Kira and Leo, are subject to the jurisdiction of revolutionary people’s courts of class justice, not objective justice, as shown when the State illegally moves a tenant named Marina Lavrova into their apartment; how Communists, like Andrei Taganov, students, like Kira Argounova, and musicians, like Lydia Argounova, are purged from their schools, jobs, and homes, for having subversive attitudes, real or imagined; how other characters, like Sasha Chernova and Irina Dunaev, are condemned to the vast gulag system;

How characters routinely spy on each other, so they can trade information to the state for some kind of reward; how the novel’s Soviet government nationalizes character’s businesses and bank accounts, before breaking into and emptying their safety deposit boxes; how the book’s Soviet Union makes Russians queue-up in endless bread-lines for rotten food that is always in short supply; how the novel’s centralized state deprives people of their privacy rights, even in their own homes; how the book’s government makes characters, like Vava Milovskaia and Sonia Presniakova, raise their children in state-run day nurseries – like the Young Pioneers, for example, or the Teenage Komsomol, for instance – since, the family is an institution of the past, according to the book’s many Marxists.

For a full-summary of Emre’s 512-page book, please read my 20-page introduction located inside the book. So, you can learn about many other topics Emre’s book analyzes, as well. (Other subject matters that are not mentioned in this brief synopsis).

This book is especially timely, given the current war between Russia & Ukraine. Since it analyzes, in its 200-page annotated bibliography, how Ukrainian peasants fought against Soviet collectivization. So, they could reclaim administration of village affairs, retrieve their confiscated tools and cattle, destroy the collective farming system, reintroduce free trade, reopen churches, restore all goods to Ukrainian farmers, get back peasants who were deported, and abolish Soviet power in Ukraine. So, the Ukrainians could regain their national independence.

Synopsis (Preface Soviet Ukraine):

This book is especially timely, given the current war between Russia & Ukraine. Since, it analyzes, in its 200-page annotated bibliography, how Ukrainian peasants fought against Soviet collectivization. So, they could reclaim administration of village affairs, retrieve their confiscated tools and cattle, destroy the collective farming system, reintroduce free trade, reopen churches, restore all goods to Ukrainian farmers, get back peasants who were deported, and abolish Soviet power in Ukraine. So, the Ukrainians could regain their national independence.

Gurgen’s book is also well-timed because it examines how Ukrainian characters are forced to work collective farms, primarily in the black earth regions of Ukraine. So, Russians can sell the food they produce to the free West. Ultimately, showing readers how destructive the collective farming system is for Ukrainian peasants who are trying to be good farmers.

This book is also timely because it analyzes how We the Living dramatizes the 1920 Battle of Melitopol, which was a military engagement between the armed forces of Ukraine and the armed forces of the Russiancity of Melitopol. Also, because it examines how Ukraine’s Donetz Basin produced 3/4’s of Russia’s coal output before the revolution, yet deteriorated rapidly after the war due to Soviet mismanagement.

Emre’s essays are also timely because they reveal how Russia raised money for super-industrialization by stealing the crops of Ukrainian farmers who were forced to work the fertile black earth country of Eastern Ukraine.

Also, this book is relevant because it shows readers how in 1918 the Soviets were afraid of the Ukrainian national government, because it fought with Cossack troops, the White Army, the German Army, and the Czech Legion, against them.

Further, this book is connected to today’s headlines because it examines how Nester Makhno, a Ukrainian military commander (born in Hulyaipole, Ukraine) fought against Soviet influence in towns under his control. Sometimes leading large Ukrainian peasant armies that numbered in the tens-of-thousands.

Besides analyzing Nester Makhno and the Makhnovists, Gurgen’s book also analyzes how the Soviet empire enlisted millions of Ukrainian slaves to work the great industrial and mining regions of Ukraine; how harsh Soviet policies were used by the Bolsheviks to force 120,000 Ukrainian miners to fulfill their steel and coal quotas. Since the Soviets equated any work absenteeism with expulsion to a camp, or a death sentence, in a gulag.

Gurgen’s book is also unique because it shows readers, in the context of Ukrainian mining, how the Soviets increased the work-hours of Ukrainian miners laboring in the Donetz Basin; how Ukrainian miners were blackmailed by the Soviets to increase their work productivity; how miners ration cards were confiscated by Georgy Pyatakov, when he was the top Soviet Director of Ukrainian Mines; how Ukrainian miners were not given clothes and shoes, which led many workers to share their coats and boots (during their lunch break, or after their shifts); how non-working families of Ukrainian miners were expelled, so the state had less mouths to feed; and, lastly, how the ration cards of Ukrainian miners’ families were also confiscated.

Further, my bibliography analyzes how the Soviets kidnapped Ukrainian engineers and technicians by falsely accusing them of industrial sabotage. So, the Soviets could appropriate skilled Ukrainian engineers for high-profile construction sites and civil-engineering projects located in Soviet Russia. Thus, from 1930-1931, 48 percent of all Ukrainian engineers in the Donbass were either dismissed (or arrested) on charges that they were responsible for industrial accidents, frequent breakdowns, and an overall decline in the quality of production.

Another topic my book explores is how requisitioning detachments were sent to Ukrainian cities, towns and villages, seizing everything in sight, including stew from a family pot and pillows from underneath the heads of sleeping babies. Prompting many Ukrainian Kulaks and farmers to block the violent seizure of their food by creating makeshift armies of peasant resisters, which often numbered in the tens-of-thousands. Armed with pitchforks, scythes, wooden spears, axes, and sometimes rifles, these Ukrainian peasants really did burn Soviets alive (as shown in We the Living and as described in my first essay).

In fact, due to Soviet dekulakization detachments, 2.5 million Ukrainian peasants took part in 14, 000 revolts, riots, and mass demonstrations against the Moscow regime. Since these Ukrainians wanted to escape the jurisdiction of Moscow’s 1932 Molotov Commission, which blacklisted all districts in which the required collection targets had not been met. (Just like they did in the Hunger Games). Ultimately, arresting and executing thousands of Ukrainian agricultural workers and farm managers suspected of minimizing production. Yet, the real reason why many farms could not reach their quotas was because of unattainable industrial targets set by Soviet authorities.

Besides analyzing the seizure of Ukrainian food, Gurgen’s book also outlines how the Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932-1933 resulted from the rural population’s resistance to forced collectivization. Resulting in the premature death of 6 million Ukrainians in the span of only a few short months. For the Soviets systematically used man-made famines against Ukrainians to get them to comply.

Next, Gurgen’s book describes how Soviet Russia tried to gain Western support for collectivized farming by staging propaganda farm tours to places like Soviet Ukraine. So, Western diplomats would tell the world about the glory of collectivized farming. To this end, a selective farm tour—to Ukrainian children’s gardens—is given to a French senator named Edouard Herriot. So, he reports to Western journalists that Soviet “Ukraine [is] full of irrigated, cultivated fields resulting in magnificent harvests”. Sadly, this French senator only visited a model Ukrainian children’s garden. If he had been shown all of Ukraine’s collectivized fields, he would have realized that 4 million Ukrainian peasants died working shriveled public lands.

This book also claims – in its bibliography – that because Mikhail Gorbechov was born into a poor peasant family of Ukrainian heritage, he saw, firsthand, what was being done to Ukrainian peasants on collectivized Soviet fields. Thus, because Gorbechov worked collectivized farms himself for many years, he saw, for himself, how badly Ukrainian farmers were treated. Thus, when Gorbechov became the General Secretary of the Communist Party, he could not stand idly by while his former countrymen were exploited. Since, before joining the Party, Gorbechov saw farm atrocities himself when he drove tractors, combines, and harvesters across collectivized fields. So, when he came to power, Gorbechov tried to restructure the Communist Party. Through glasnost (opening) and perestroika (restructuring). For Gorbechov’s modest upbringing, characterized by difficult farm work, made him sympathize with Soviet Republics, like Ukraine, who were struggling to grow food.

Further, Gurgen’s bibliography also shows readers how the Soviets arrested thousands of Ukrainian intellectuals for having transformed (according to the Soviets) the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences into a haven for bourgeois nationalists and counterrevolutionaries.

Also, Gurgen’s book analyzes how millions of Ukrainians were deported from Western Ukraine by the Soviets. When Ukraine was annexed to Russia in 1939. At which time:

- 11, 038 members of bourgeois nationalist families were deported;

- 3, 240 members of the families of former policemen were deported;

- 7, 124 members of families of land-owners, industrialists, and civil servants, were deported;

- 1, 649 members of the families of former military officers were deported;

- 2, 907 Ukrainians labeled as others were also deported from Ukraine.

Lastly, this book outlines how the NKVD purged Ukrainian schools, so they could root out all opposition to Soviet collectivization. By leafing through the school books of Ukrainian children living in Western Ukraine. So, they could expurgate objectionable scholastic content.

Ultimately, all of this Ukrainian analysis makes Gurgen’s book highly relevant to today’s headlines. Since, it offers, from a historical perspective, a topical critique that is in-step with the current war between Ukraine and Russia.

References to Ukraine (Index): Ukraine xvii, 27, 31, 34, 226, 289, 357, 373, 383, 401, 404, 406, 409, 410, 411, 412, 417, 427, 437, 446, 447, 454, 467, 480

Ukrainian xvii, xxxix, xl, 27, 31, 33, 55, 66, 124, 176, 226, 227, 357, 373, 381, 383, 401, 404, 409, 417, 433, 436, 447, 452, 454, 471, 472

Ukrainian Food Stores 27

Ukrainian Grain 55

Ukrainian Peasants xl, 31, 33, 66, 409

Interview Questions & (Possible) Answers

(Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s We the Living)

Introduction

Since, We the Living shows readers, through personal stories—not political debate (or historical analysis)—the reality of life under Soviet Communism, Rand’s novel appeals to readers who really want to understand how Communism degrades people’s actual everyday lives. (In practical ways). As opposed to reading overly-abstract Soviet political theory—or overly esoteric Russian history—which, though replete with facts-and-statistics, does not vividly portray the impact of Communism over individual lives the way We the Living and my book does.

For most books on Russian Communism are either overly abstract, or are too concrete bound, or focus on other subject matters, or some combination thereof. But my book, on the contrary, is a stimulating read. Because it not only balances concrete examples with the abstract theory behind those examples but also because it is comprehensive, deep, and detailed, yet does not bore (or off-put) readers with floating abstractions, unexplained concretes, hair-spitting statistics, or bad prose. Rather, my book has a variety of clear and insightful theses; expert use of analysis with no useless summary; textual evidence, including references to and quotations from the text that are interpreted rather than just cited; paragraphs that are unified, coherent, fully-developed and in logical order, and, lastly, eloquent arguments that are not only grammatically correct but stylistically superb, especially in terms of clarity.

“Besides being well-written, from the perspective of someone who actually lived under communism, Gurgen’s book is also different than the competition. Since, besides having essays, his book also has a 200-page annotated bibliography that summarizes 75 books, essays, videos, documentaries, journal articles, speeches, and presentations, in a unique back matter section. A section that is useful for people who want to read more on We the Living and Soviet Communism, from a comprehensive and significant perspective. So, they can clarify their understanding of both We the Living and Russian Marxism.

In sum, my unique intellectual contribution to We the Living and Soviet Studies is the ability to explain both in clear and moving ways. Through a lengthy introduction, a set of unique essays, and an extensive bibliography.

Target Audience

My book’s target audience are fans of Ayn Rand, aspiring Objectivist pupils, students of Soviet history, and people who want to better understand how Soviet and Ukrainian history fostered the present hostility between Ukraine and Russia.

A Reference Guide to Ayn Rand’s (We the Living)

Cover: * Coming Soon (Mid 2026)

Tagline: “Fully comprehensive Reference Guides”

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: May, 2026 (estimate)

Page Count: 600 + pages

ISBN #’s: ???

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: ???

Purchase Links: Unavailable

Synopsis:

Gurgen’s Reference Guide, on Ayn Rand’s We the Living, is fully comprehensive, while his competitors' study guides are relatively brief. For Emre’s Reference Guide unifies and condenses most of We the Living’s raw book data. While other study guides—though well-written and useful—only summarize the book, analyze a few main characters, a few themes, and not much else. But Emre’s Reference Guide analyzes it all.

`Specifically, Gurgen’s Reference Guide connects most of We the Living’s raw data points to specific occurrences in Soviet history. Thus, making Gurgen’s book is the only study guide on the market that is fully comprehensive. Because while most other study guides are still good, they only analyze a few characters, a few themes, not much else. But Gurgen’s Reference Guide analyzes it all. Thus, making it easier for scholars to find the specific information they are looking for. So, they can form, support, and defend their own theses.

Specifically, Gurgen’s Reference Guide analyzes We the Living’s 18 major character sand 95 minor characters, before noting the book’s 5 major newspapers (The Living Newspaper, The Krasnaya Gazette, Moscow Izvestia, Pravda, and The Wall Newspaper). Further, it describes Petrograd’s 3 main theaters (The Alexandrinsky Theater, The Mikhailovsky Theater, and The Marinsky Theater) before examining the book’s 3 main social parties: Vava Milovskaia’s fashion party, Victor Argounova’s engagement party, and Pavel Syerov’s wasteful bacchanalia. Additionally, it notes the novel’s 5 Marxist social clubs: The Marxist Circle; The Marxist Library Club; The Marxist Art Academy; Worker’s Clubs; and Party Clubs. Before examining the novel’s 5 types of schools: factory schools, labor schools, Red Universities, Rabfacs, and the Technological Institute. Gurgen’s Reference Guide also describes the novel’s 2 types of stoves—Primus Cooking Stoves and Bourgeois Stove Heaters—before depicting the book’s 2 Soviet youth groups—The Young Pioneers and The Teenage Komsomol.

Moreover, Gurgen’s book describes the story’s 4 modes of transport —trains, trams, cabs, and sleds—as well as the book’s 3 major markets—the Alexandrovsky, Nikolaevsky, and Kouznetzky markets. Further, Gurgen’s Reference Guide depicts the novel’s 2 main restaurants and cafes: The European Roof Top Garden and Café Diggy-Daggy. Afterwards, it defines Petrograd’s 2 main city districts: The Putilovsky Factory District and the Viborgsky Restaurant District. Then, it catalogues Petrograd’s 2 major promenades: the Nevsky Prospect and the Kamenostrovsky Prospect. Before defining the book’s student blood purges, which take place at the Technological Institute, the University of Saint Petersburg, and at Petrograd’s Red Art Academy.

Further, Gurgen’s Reference Guide scrutinizes the book’s Ukrainian locations – like the Donetz Basin, for example, or the Crimean Peninsula, for instance – ultimately tying these places into a historical analysis of the Soviet Empire.

It also analyzes why Rand changed her book’s name from Airtight to We the Living; why Soviet characters, like Andrei Taganov and Stephan Timoshenko kill themselves out of despair; how the novel’s 13 songs complement the book’s plot-action; how the city of Saint Petersburg is described in the novel; how Ayn Rand depicts nature, weather, and the sky, in We the Living; why St. Petersburg’s name was changed to Petrograd, then Leningrad, then back to St. Petersburg, again, and why this is important; why Russia moved its capital from St. Petersburg to Moscow because they felt threatened by Europe; why Emre’s Reference Guide not only examines We the Living’s various modes of transportation—cabs, sleighs, and trams—(in great detail) it also examines the book’s two main train rides: from Petrograd to the Crimea; then again from Petrograd to near Latvia. Before describing Leo’s train ride to Yalta, Antonio Pavlovna’s train ride back from Yalta, and Kira’s train voyage to the Latvian border.

Saint Petersburg was built on a swamp atop the bleached bones of thousands of soldiers; how the book’s winters, springs, falls, and summers, are described, and what they mean in the story; how Rand describes the book’s different sunrises and sunsets and what they mean to characters; how the Czars—i.e. Alexander III & Catherine II—are depicted in the novel and what this means; how various Czarist institutions, imperialist buildings, monarchical prisons, stately statues, royal possessions, and kingly regalia, is shown in We the Living, and how this complements the novel’s plot action; how the civil war between the Red Bolsheviks and the White Monarchists is also shown in We the Living and why this is important; how Stalin’s New Economic Policy manifests in the book and what this means; how a tricky merchant, named Karp Morozov, a Soviet railroad official, named Pavel Syerov, and a former aristocrat, named Leo Kovalensky, steal, (then sell) the people’s food; how characters trade their personal treasures at flea-markets and swap-meets to survive; how hyperinflation make characters Rubles – and Kopek coins – lose half their value overnight; how factory owners, private traders, unemployed bourgeoise, and former aristocrats are made to pay more rent, more for building repairs, and are forced to shovel snow, because they refuse to work for the State; how We the Living systematically undercuts Christianity by destroying churches, converting church’s into Lenin libraries, and by killing priests.

Similarly, Gurgen’s Reference Guide analyzes how the state destroys symbols of competing power systems (Christianity, Paganism, Monarchy, & Capitalism) to dismantle a social system that values Russians as individuals, not as members of “rightless” collectives.

Further, Gurgen’s Reference Guide examines how We the Living’s collectivized characters cherish Western values and culture. Since the story not only features Western opera halls, Western movie theaters, Western book stores, Western restaurants, and Western fashion products (such as scarves, stockings, and perfume) it also analyzes how characters defect, or try to defect, to Western lands. By either taking a smuggler ship to Berlin, Germany (Kira & Leo), or by crossing the Latvian Border (Kira), or by saving speculation money so they can buy their way out of Russia (Leo & Kira), or by taking a train to Baku, Azerbaijan (Irina & Sasha), or by trying to defect by securing a foreign assignment (Andrei).

Additionally, Gurgen’s book analyzes the novel’s ultra-minor, one-line characters. Background characters, like “We the Living’s” cooks, farmers, janitors, porters, sailors, soldiers, maids, toilers, housekeepers, sled-drivers, cake sellers, cookie sellers, flower sellers, program peddlers, newspaper criers, tram drivers, tram conductors, steel workers, burglars, hold-up men, foreign delegates, pallbearers, restaurant patrons, homeless tunnel dwellers, and prostitutes.

Next, Gurgen’s Reference Guide outlines the fate of the novel’s many peasants. By analyzing how these peasants food is seized by requisitions detachments; how peasants must assimilate to Soviet culture by attending House of the Peasant excursion meetings (on their summer vacations no less); how peasants are forced to go to the Museum of the People’s Revolution to learn that toil is noble; how farmers must watch, on their rare summer vacations, Soviet operas that teach farmers to love their chains; how peasants rebel against Soviet indoctrination by slaughtering Communists who try to seize their food. Sometimes, even burning Soviet agents alive, by first locking them in barns, then setting fire to their Soviet clubhouse, then singing to drown out their final death screams.

Most importantly, Gurgen’s Reference Guide notes how the novel’s Soviet government forces characters to eat semi-rotten powered eggs because of a fresh egg shortage; to only eat dried fruits because of a fresh fruit shortage; to consume only dried vegetables because of a fresh vegetable shortage; and to not eat beef, chicken, fish, and other viands, because of a fresh meat shortage. Gurgen’s book also examines how the novel’s government compels characters to eat rotten millet, moldy flour, and rancid sunflower seed oil. Because only these spoiled foods are readily available at the local co-operative. Likewise, due to a sugar shortage, characters must sweeten their tea with black-market Saccharine, which ultimately gives characters bladder cancer. Further, characters must not only eat pancakes made from coffee grounds and linseed oil, they must also wolf down frozen potatoes, in train bathrooms, since these frozen spuds are a rare, stealable, luxury.

Gurgen’s Reference Guide also notes that to get this food, characters must wait in endless lines, at State co-operatives, communal kitchens, and other provision centers, where they are exposed to harsh Petrograd weather, including strong winds, freezing ice, blinding snow, cold sleet, driven rain, and large hail. Weather that causes Petrograd residents to contract frostbite, open sores, respiratory infections, joint pain, dry skin, sore throats, colds, and flues. Weather that exacerbates a character's pre-existing medical conditions, like high blood pressure, diabetes, and vascular diseases, thereby turning non-fatal medical conditions into life-threatening health emergencies. As Russians queue up for hours in all-weather winter conditions, waiting for their meagre rations.

Other topics Gurgen’s Reference Guide examines include: how train speculators smuggle black market food into Petrograd; how the novel’s Soviet State causes characters to die from easily preventable diseases, like cholera, typhus, scurvy, glanders, and lice; how the book’s Soviets pollute Russia’s cities, towns, villages, and countryside; how the book’s government tries to displace a parent’s right to raise their own children by creating two parallel youth groups—The Young Pioneers and the Teenage Komsomol—where Soviet allegiance trumps parental guidance; how State Communism creates a climate of paranoia amongst We the Living’s characters by making them constantly watch each other to discover information they can trade to the government for some type of reward; and, lastly, Gurgen’s Reference Guide shows readers how anti-western propaganda infests We the Living’s many pages.

Above all, Gurgen’s Reference Guide outlines how We the Living’s Soviet State loots their citizens wealth by nationalizing characters businesses, homes, and bank accounts. Then, robbing their safety deposit boxes, gold pieces, silver spoons, and jewelry. Making characters sell their last remaining possessions in state-run valuta (or torgsin) shops, where food can only be bought for family heirlooms, personal treasures, and foreign currency.

For a full summary of all the contents of Gurgen’s Reference Guide, please read – when available – his book’s 29 page, 10, 976-word, introduction.

The Fountainhead Reference Guide: A to Z (2nd Edition Narrative Version)

Testimonial: Amazon Review (5 Stars)

Tagline: “Fully comprehensive Reference Guides”

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: 10/10/2019

Word Count: 195, 374

Page Count: 596

ISBN #’s

- ISBN: 978-1-7283-3073-0 (Hard Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-7283-3072-3 (Soft Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-7283-3071-6 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: $38.99 (Hard Cover); $28.99 (Soft Cover);

$9.99 (E-Book)

Purchase Links

Synopsis:

Gurgen’s Reference Guide takes the form of a Fountainhead encyclopedia with several independent sections: a complete dictionary of the book’s 152 characters; a dictionary of relationships between all of the book’s characters; a lexicon of the book’s 37 buildings; a catalogue of the books 4 newspapers, 5 magazines, and 1 tabloid; a listing of the novel’s 20 groups of people (organized into 15 different associations); a timeline of the book’s events; a classification of The Fountainhead’s symbols; and a dictionary of the novel’s locations. Further, it also unpacks The Fountainhead’s themes, plot, characters, and settings in a lengthy analytical section. With 93 different analytical points.

Lastly, Gurgen’s Reference Guide offers a chronology of Rand’s life-and-works, a glossary of architectural terms, and a back-matter spreadsheet of Objectivist Intellectuals who have written about Ayn Rand. Including who they are, what they have written, where they have studied, their organizational affiliation, their contact information, and more.

At 596 pages, or 195,000 words, Gurgen’s Reference Guide makes a significant intellectual contribution to our understanding of The Fountainhead.

The Fountainhead Reference Guide: A to Z (Brief Version)

Tagline: “The basics of what you need to know.”

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: 12/15/2021

Word Count: 38,372

Page Count: 136

ISBN #’s:

- ISBN: 978-1-7283-6894-8 (Hardcover)

- ISBN: 978-1-7283-64939-1 (Softcover)

- ISBN: 978-1-7283-6438-4 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: $23.99 (Hard Cover); $13.99 (Soft Cover);

$9.99 (E-Book)

Purchase Links

Synopsis:

This short version of my Fountainhead Reference Guide summarizes, in one sentence, the essence of the book’s 152 characters; explains their makeups in 91 analytical writings; defines 39 architectural words in a back-matter glossary; and organizes the thinking of 58 Objectivist Intellectuals into a spreadsheet. By name, title, degree, profile, work, year, publisher, and location. Further, this book’s back matter also has a list of works that I used to research my full reference guide.

Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s the Fountainhead

Testimonial: Amazon Review (5 Stars)

High-Quality Analysis of Seminal Novel

"Well-written, extremely well-researched, scholarly collection of essays on what the author calls 'the greatest American novel ever written'. I tend to agree. This book is thoughtful, searching, and a pleasure to read. And it enhances one's enjoyment of the classic 1943 novel itself."

(* Verified Amazon Purchase)

Tagline: ““What is means to be an American.”.”

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: 10/10/2019

Word Count: 46,781

Page Count: 136

ISBN #’s:

- ISBN: 978-1-6655-6689-6 (Hard Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-6655-6688-9 (Soft Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-6655-6687-2 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: $23.99 (Hardcover); $13.99 (Soft Cover); $9.99 (E-Book)

Purchase Links

Synopsis:

Critical Essays on Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, by Emre Gurgen, shows readers how The Fountainhead is the greatest American novel of all time. Because it links the creative spirit of Americans to the progress of human civilization. By showing readers that human beings advance as a species because of the efforts of people who are not second handers. Creators, innovators, and discovers, who move society forward—who fuel the engine of progress—because they follow their own ideas and insights instead of relying on what others think and believe.

Thus, to analyze the Fountainhead’s meaning of American individualism—specifically how egoism, selfishness, and uniqueness, leads to human progress— Gurgen’s first essay—titled How the Fountainhead Expresses America’s Founding Values—shows readers how a tough looking jury of twelve free-thinking Americans individuals acquit Roark for blowing-up a governmental housing project. Since, it was not designed according to Roark’s blueprints. Even though he had a contract with the government—through Peter Keating—giving Roark ultimate design authority. However, because the government alters Roark’s design by adding several distortions, he destroys Cortlandt Homes. Rather than see his building disfigured. Since, Roark cannot sue the government, due to the doctrine of Sovereign Immunity, which says that the government cannot be sued by citizens, during its normal course of duty. Thus, this sovereign immunity not only shields government builders of low-income housing projects it descends from the British idea that “the king can do no wrong.” Which, in The Fountainhead, generally means that Roark cannot sue the U.S. government for liability for their official actions.

So, to get justice, Roark chooses a hard-looking jury, made-up of “two executives of industry, two engineers, a mathematician, a truck driver, a bricklayer, an electrician, a gardener, and three factory workers” (707). Logical Americans who unanimously decide that Roark deserves to be paid and valued for his work, just like they do (707). For this jury likes the American values Roark expresses in his Cortlandt speech. Namely, that America is a land where people are free to work, act, think, and behave, according to their own best judgment, without undue governmental, social, and interpersonal interference. A land where a person’s individual architectural rights will be honored.

Evidently, Roark’s moving courtroom speech, about the sanctity of the creative mind, is successful because it asks these jurors to “rediscover their own Americanness.” (Den Uyl). To “search their own consciences for the truth that lies within them.” (Den Uyl). Thus, because Roark appeals to American values to clear him of any wrong doing, the jury’s delivers Roark a “not guilty” verdict. Since, this jury thinks that Roark deserves to be paid and valued for his work, under the terms of his contract. Thus, Roark’s acquittal, reaffirms the basic-wisdom of free-thinking American individuals through juris prudence.

Another way Gurgen shows readers how Ayn Rand expresses Individualism in The Fountainhead is by analyzing a construction worker named Mike Donnigan. Because he is a unique American individual, with his own distinctive being. For Mike bases his identity on what he thinks himself. Not on what his co-workers, bosses, or fellow construction guilders say is so. Since, Mike uses his mind, to the best of his ability, to evaluate people, situations, and events objectively. According to facts, evidence, and proofs related to them. Based on what he sees himself. Thus, because Mike makes up his mind for himself—based on what his eyes tell him—he thinks that Roark is not “a stuck-up, stubborn, lousy bastard,” as Roark’s cite supervisor claims (86). But rather that Roark makes friends with people if he thinks they can help him build better. This is why Mike realizes that Roark associates with people not because they have money, status, power, and prestige. But because they are worthy human beings who can help him build well. As such, Roark drinks beers with Mike at a basement speak-easy. Where Mike tells Roark “his favorite tale of how he had fallen five stories when a scaffolding gave way under him, [and] Roark speaks of his days in the building trades.” (86). If Roark thought it beneath him to befriend a working man who shares his passion for building he would not have gone to a pub with Mike. But, he does. And, Mike loves him for it. For Mike realizes that Roark befriends people not because they are rich, or powerful, or influential, or well-connected. But because they have good characters.

Another way Gurgen’s book shows readers how The Fountainhead expresses the American ethical theory of life—which says that the highest good for man consists in realizing and fulfilling his full potential, so he can actualize his ideal or real self—is shown when Mike Donnigan travels around the country in his “ancient Ford” truck building how he wants to build with Roark (86). Since, working with Roark on a series of matchless structures—like the Heller House, for example, or the Aquitania Hotel, for instance—reinforces Mike’s identity. Since, constructing magnificent buildings with Roark imbues Mike with a feeling of pride and accomplishment for the great creative work that he can do.

Further, Gurgen’s book examines how The Fountainhead’s American reading public praised the story for connecting to their sense of what it means to be a good American and a good human being. For middle-class fans from all class backgrounds, businessmen from all social strata, lawyers from all walks of life, industrialists from all circumstances, students from different schools of thought, and soldiers from different marshal ranks, all loved The Fountainhead. For they all felt that the novel inspired them to achieve great things in their own lives. By exercising their unique individual wills to realize their own singular goals. Accordingly, cadets, privates, airmen, lieutenants, enlisted men, hotel owners, merchants, congressmen, senators, writers, journalists, novelists, literary agents, artists, and students, of every strip and variety, felt that The Fountainhead was a great work of American literature.

American readers felt this way because they thought that The Fountainhead encouraged Americans to fully discard the doctrine of altruism and self-sacrifice as an ideal, so they could find a different positive faith in humanity. Also, because it helped them clarify their views of their own lives, thereby aiding them in their moral decisions. Since, reading The Fountainhead gave them hope when they felt unhappy. Because it provided emotional fuel for individualist writers, so they did not feel so intellectually lonely. Also, because the story’s individualistic ideals equipped university students with the intellectual ammunition they needed to face their forthcoming collectivist college years. Thereby, reinforcing people’s values by reaffirming their individuality. For many minority voices were stimulated by The Fountainhead. Since, they were in complete sympathy with Ayn Rand’s ideas of individualism. Since, the story’s hero, Howard Roark, represents individualistic qualities that these readers could admire and aspire to themselves. For Rand’s Objectivist philosophy, as shown through her characters, defended people’s right to make (and retain) their own just profits. By representing characters making honest money in a capitalist democracy. Further, American readers loved reading The Fountainhead because it supported their work ethic. By depicting many characters working 7 days a week, for 10 hours, or more, a day. They also loved the story, because it claims that one’s own industry, productivity, truth, and vision are the means by which they advance their lives. Lastly, many Americans persuaded themselves to read Rand’s book, since they wanted to know where Ayn Rand drew her ideological strength from. So, they could choose a profession that meant as much to them as writing The Fountainhead did for Ayn Rand.

Specifically, American soldiers felt that The Fountainhead justified why they fought in World War II. To protect their civil liberties. By not only showing troopers what a free society looks like but also by showing soldiers how a free nation becomes a dictatorship. This is why after many bombing raids by the United States’ armed forces, “air force pilots would gather around a candle and read passages from The Fountainhead.” (Ralston). To remind themselves that they were fighting to protect their own individual freedoms. From the encroachments of the evil axis powers, who were trying to turn them into exploited slaves, with no right to the fruits of their own freedom, including their own private property. In fact, “one soldier [even] said that he would have felt much better if he thought that the war was being fought for the ideals of The Fountainhead.” (Ralston). For most soldiers felt that if America fell to the military, socialist, fascist, or theocratic dictatorships, perched on its ideological doorstep, then it would be impossible for them to live free lives as dignified human beings. In-line with their own individual truths, visions, and life-paths. Thus, American soldiers celebrated The Fountainhead. Because it reminded them of what a free nation looks like, and why it should be protected.

Next, Gurgen examines how The Fountainhead not only drew in American readers by dramatizing American human progress but also how it attracted international readers, as well. Who were likewise activated by Rand’s depiction of universal human values, such as integrity, productiveness, honesty, independence, reason, purpose, and self-esteem. Since, foreign readers living in other countries also wanted to understand how innovation moves life forward. Such a foreign call for Ayn Rand’s straight talk, then, resulted in The Fountainhead being translated into 25 languages—Albanian, Bulgarian, Chinese, Croatian, Chezch, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Mongolian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovakian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Ukrainian. For international readers, especially people who share American values, wanted to read The Fountainhead in their native tongues. So, they could understand, through fiction, what proper and improper selfishness is.

Further, because Gurgen’s book examines the concept of social mobility in The Fountainhead, of rising up in society because of what you have created, it appeals to America’s blue-collared workers who also want to become rich and successful. Since many plain workman, it can be reasoned, would benefit from reading a book that shows them, in specific ways, how they can improve their own lives. By exercising their own values in a merit-based civilization that enables people to rise up in society, by creating various enterprises. So, they can ascend to the rarefied heights of a classically liberal civilization. By advancing themselves, materially, socially, metaphysically, and existentially, on the strength of their own efforts. Based on the capacity of their own minds.

Such a meritocratic civilization, where ordinary people can rise up in life, is shown when Ayn Rand depicts the modest beginnings of an American businessman named Roger Enright. Who, though born dirt poor in a one-room hovel, achieves life success, through his own industry. For though Enright starts life as a modest Pennsylvanian coal miner, eventually he climbs out of the bowels of the earth by saving a modest capital sum. Then, by re-investing this money in the company’s oil business. Eventually, even buying out its other owners. For under Roger’s able leadership, this oil company becomes even more profitable. Eventually, because Roger makes great profits from this oil company, he becomes a multi-millionaire, solo-preneur, who invests his money in 7 other enterprises: a publishing house that prints and illustrates people’s books; a diner that delivers patrons clean food at a good price; a radio shop that sells stereos to customers, so they can listen to information they need, or want, like news, music, & sports; an auto-garage, which fixes peoples cars at an affordable price; a plant manufacturing electrical refrigerators, so consumers do not have to store their cold foods in a messy ice-box; an apartment building called the Enright House, which enables residents to live in sane comfort; and a private housing project called Cortlandt Homes, which offers low-income residents (or anyone who wants to buy there) a reasonably priced option. To build these businesses, Enright “works twelve hours a day” with “ferocious energy, coining money where nobody else thought it would grow.” (256, 258). Thus, because Enright works hard to materialize his own business vision, he makes himself a multi-millionaire in a few years. Who has improved the quality of his life greatly. Due to his own self-made efforts. Despite starting life as a poor workman who risked contracting black lung (from coal powder) and risked being buried alive (in cave-ins) from unstable cave supports.

Such a dramatic example, then, of a human being rising up – in life – by working hard and thinking for himself, shows blue collared workers (everyone really) that though they may be born a poor nothing, they can make themselves a great something. By working smart and hard over many years. Just like Roger Enright did.

Other topics Gurgen’s first essay explores include: how Roger learns from his business mistakes, instead of letting his frustrations and failures lower his self-esteem; how the skyscraper is an example of the American creative spirit in motion; how Henry Cameron is the father of the modern skyscraper and what this means; how the relationship between the novel’s hero-protagonist Howard Roark and the teacher whom he has selected and from whom he will get the proper training, Henry Cameron, represents an American mentor-mentee relationship; how Howard Roark builds his career as an architect, despite many people trying to tear him down; how Howard Roark makes a sculptor named Steven Mallory feel valued and appreciated by hiring him, so he does not feel like an unrecognized genius all the time, or something much worse, the genius who is recognized yet rejected; how an honest American journalist named Austen Heller, serves as a foil to Gail Wynand, a corrupt media man; and, lastly, how the Fountainhead is the great American novel because it essentializes American individualism.

Next, Gurgen’s 2nd essay, titled Roark the Life Giver: How Howard Brings Out the Best in Like-Minded Others, analyzes how Howard Roark inspires, indeed, revitalizes, many of the Fountainhead’s characters. By inspiring a young man to compose his own symphonies. Until this youth can bring his musical values into the world, just like Roark brought his architectural values into reality. Also, by enthusing his apprentice architects (at the office), his able draftsman (at their desks), and his brave construction workers (out in the field), by being a builder, a visual designer, and a civil engineer of the greatest quality. Who inspires his employees to excel in their own lives by being true to themselves. Similarly, Roark assists his lover, Dominque Francon, to go from a malevolent view of society and man’s place in it, to a benevolent view of reality, and other human beings. By showing her that other people cannot stop him from building his own unique way. Likewise, Roark spurs a corrupt journalist, named Gail Wynand, to revitalize his basic essence. By bringing first hand values into his life. Similarly, Roark shows a genius sculptor named Steven Mallory that despite being poor and not having much work, eventually Mallory will rise to greatness. When other greater geniuses, like Gail Wynand, value his sculptural abilities. Relatedly, Roark shows an able electrician named Mike Donnigan that the world eventually rewards outstanding builders—even if they are not valued and recognized for decades—if they abide by their own unique architectural vision in life. By staying the course of their own career trajectory, despite heavy social opposition and collectivist weapons, pitted against them. Subsequently, Roark also shows a corporate middle-man name Kent Lansing that he can realize his own unique values in life by fighting to implement Roark’s blueprints for his Aquitania Hotel. Since by designing this hotel, Howard helps Kent realize his goal of making his hotel management corporation a lot of money. Lastly, Roark helps a solo-preneur named Roger Enright realize his goal to create worthy businesses. Because Roark designs The Enright House and Cortlandt Homes, despite the public’s loud outcry.

Above all, Roark inspires readers to excel in their own lives by showing people a believable fictional example, in the flesh-and-blood, of a credible literary character living out his own values.

Lastly, my 3rd, and final, essay, titled Individualism & Capitalism Versus Collectivism and Communism in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, shows readers that only in free civilizations, like the Fountainhead’s America, can people really excel, by pursuing their own values. While in unfree countries, like Soviet Russia, Fascist Italy, and Socialist Germany, people stagnate, or move backwards, in their lives. Because they are told not to live for themselves, by building and profiting from their own lives. But rather are told to live for various collectives, instead. Collectives, like the State, in Soviet Russia, the nation, in socialist Germany, or the mob, in Fascist Italy. Since, in these dictatorships, the State actually blocks people from realizing their best spiritual, moral, and economic selves. By placing anti-capitalist groups of collectives above their own citizen’s self-interests.

Similarly, Gurgen’s book shows readers how The Fountainhead’s characters can make themselves happy by not only having a self—which they are proud of—but also by exercising that self. By deploying capitalism to improve their lives. Accordingly, many of The Fountainhead’s characters, such as Roger Enright, for example, or Jimmy Gowan, for instance, are staunch individualists who want to improve their lives by exercising capitalism. By creating healthy businesses that deliver their customers tangible material values. For Jimmy Gowan is a plain auto-mechanic, who becomes an owner of a very profitable filling station (after fifteen years of back-breaking) while Roger Enright is a coal miner, who saves enough money to open an oil business, a publishing house, a restaurant, a radio shop, an auto-garage, and a plant that manufactures electric refrigerators. Evidently, both these characters better their lives by exercising free-market capitalism.

Concomitantly, my third essay analyzes how a Marxist intellectual, named Ellsworth Toohey, seeks to turn America into a Soviet style Communist dictatorship. By arguing in Socialist magazines—New Voices, New Pathways, New Horizons, and New Frontiers—that humanity needs to originate and deploy a comprehensive form of collectivist ethics, which can only be achieved through a collective economy. Here, Toohey realizes that if he can “take control of humanity’s economics—[which is] concrete and accessible—[he] can hope to control humanity’s spirit.” (Rand). Similarly, to discredit the economic importance of individuals in favor of the economic significance of the masses, Toohey pens a book named Sermons in Stone, in which he tries to collectivize American architecture by glorifying the contributions of the common man to this art. Another way Toohey tries transmogrify America into a Marxist State is by counseling his students to become socially minded State citizens concerned with the social welfare of the community. (Not with the advancement of selfish capitalists, who he thinks only care about themselves). Toohey does this by becoming a vocational adviser in an unnamed New York University, where he advises his students to not pursue their spiritual passions – as they want to. But to pursue, instead, a practical, sensible, profession that they can be “calm, sane, and matter-of-fact about, even if they hate it.” Toohey says this so he can turn his students into socially-minded State citizens who are concerned with the social welfare of the community, not pupils who only care about their own personal, selfish, happiness. Not egotistical students who disobey Toohey because their selfish interests overrides his counsel. But compliant students who Toohey can deploy in later life, to rise to wider-and-wider levels of power off their backs. So, he can use this community of student followers, this collective of yes men, to become the president of the United States. So, Toohey can turn America into a Marxist dictatorship, in his mad quest to become “a physical killer, not just a spiritual one.” (Bernstein).

Similarly, Toohey also prepares America for a Communist dictatorship by maligning free-market capitalism. He does this by writing a Daily Banner Column called One Small Voice. Where he concerns himself not with the individual-creation of great artists and capitalists. But with the collective-production of bad artists and socialists. Who all express, in their works, a virulent form of group-think dedicated to the destruction of individual greatness. Similarly, Toohey spreads anti-capitalist messages in the Wynand Papers. By writing that people’s “personal motives are always ‘goaded by selfishness’ or ‘egged on by greed.” (615). He also has the Banner’s “crossword puzzles [define] ‘capitalists’ as ‘obsolescent individuals.” (615). Here, Toohey uses the Daily Banner to not only attack capitalism but he also uses this newspaper to popularize a newfangled form of anti-capitalist slang that is anti-mind and anti-reason. Since, Toohey’s marshals a glut of anti-American, anti-individualistic, collectivist rhetoric in his hateful column.

Toohey also tries to usher in a Marxist America by staging a hostile take-over of Wynand’s Daily Banner. So, Toohey can leverage the Daily Banner to reach wider-and-wider levels of power. So, Toohey can use Wynand’s conservative media empire to promote collectivist causes that will bring him political and social control. So, Toohey can spread Marxist rhetoric through Wynand’s top media publication, which is a large New York City newspaper with a circulation of about 8.3 million people. So, eventually, Toohey can convert America into a Marxist dictatorship. By seizing the bully-pulpit of the presidency when the time is right. When the right psychological moment presents itself. Toohey does this in 5 main ways. First, Toohey convinces The Banner’s employees to strike en masse. Second, Toohey persuades the Banner’s top sponsors—Vimo Flakes, Toddler’s Togs, and Ferris & Symes—to stop advertising in the newspaper. Third, Toohey orchestrating a We Don’t Read Wynand campaign. By bad-mouthing Roark in print, at movie theaters, even at cocktail parties. Further, Toohey tries to take over Wynand’s Daily Banner by persuading a rich man named Mitchell Layton to buy a large chunk of the newspaper. So, Layton can buy Wynand out when the time is right. In addition, Toohey arranges for the Banner’s outstanding drama named Jimmy Kearns to be displaced by a talentless hack named Jules Fougler. Since, Jules Fougler is Toohey’s hand-picked stooge who will follow his marching orders, precisely; to a tee. For Toohey’s plot to take over The Banner depends on him being able to control the scene unopposed.

Evidently, since Ayn Rand saw collectivism overwhelming the world during her life-time, she wrote a book that exploded popular group concepts prevalent in her time. She did this by undermining, in The Fountainhead, the rising collective trends of the early 1900’s. Such as the supremacy of the working class, the rule of the public interest, and the idea of subordinating yourself to something greater than yourself, like the common good. This, ultimately, is how Rand refuted the idea that a person’s duty is to selflessly serve the people, the nation, or society, instead of advancing his, or her, own selfish interests. In fact, Rand dispels the myth that collective societies are really noble experiments fueled by idealism by writing a novel that penetrates the falsehood behind collectivist dictatorships, like Soviet Russia. So, Rand wrote The Fountainhead to stop American from becoming a Communism style dictatorship. By being taken over by the Intellectual Toohey’s. Since, Rand did not want Americans thinking that communism is somehow noble.

So, Rand wrote The Fountainhead to fight against popularized collective ideas of her era. Such as the reign of the masses, the rule of a welfare state, and the idea that we are our brothers’ keepers. For Rand wrote The Fountainhead to combat the idea that global collectivism is actually good for humanity. In order to avert America’s looming collapse into full-statism and collectivization. For Rand shows in her book that group politics, especially in the arts and humanities, is a great danger to civilization. Since, identity politics, according to Rand, encourages stale thought and blind conformity. Thus, by damming collectivism, Rand suggests that America must not fall to the collectivist dictatorships that were perched on its ideological doorstep. Global tyrannies that had already subjected large parts of Europe to their despotic rule. Collective movements that had also enslaved Russia, Italy, and Germany, with collectivism of different kinds. Namely, Communism, in Stalin’s Soviet Russia, Fascism in Mussolini’s collective Italy, and Socialism in Adolf Hitler’s Weimar Germany.

Other topics my third, and final, essay studies include how Toohey’s drive to unite the globe into a Communist dictatorship encounters firm resistance by Americans. Since, unlike Europe, America enjoys capitalism and individual liberties—such as freedom of speech and religion, the right to private property, the right to earn and retain profits, and the right to emigrate—that closed countries, like Weimar Germany, Fascist Italy, and Soviet Russia, do not have.

Similarly, my 3rd essay also analyzes how people living in a capitalistic civilization—like Howard Roark, for example—are free to choose who they will be friends with and deal with in life, based on sharing like values. Whereas in Communist tyrannies—like the Marxist dictatorship that Toohey tries to establish in America—people are forced to forge social friendships based on identity politics. Because a specific person shares their race, class, gender, ethnicity, or cultural background.

My 3rd essay also examines how The Fountainhead’s worthy creations are not the product of a great many people working together. But rather are the result of several independent men working alone. Since, when Peter Keating designs buildings for the World’s Fair, he produces a disgusting hash of jumbled structures with 7 other architects. (Buildings that look like they were squeezed out of a toothpaste tube). Whereas when Henry Cameron and Howard Roark design the Dana and Cortlandt buildings alone they create esthetic skyscrapers of great architectural merit. Indeed, the comparison between pioneering buildings primarily alone, versus conforming structures mainly in a group, shows readers that when a man produces work with other people the probable result of all his compromises, appeasements, and betrayals, is something quite bad. Whereas when a person creates by himself and for himself he does better work than he can do collectively. Because he only has himself to please.

Another Fountainhead theme my 3rd essay analyzes is how individualism fosters a strong sense of personal responsibility in Howard Roark. Since, he is willing to stand alone, think for himself, and originate his own projects, almost single handedly. Because in Roark’s world it is clear who is connected to the results of a given project, or to the consequence of a given idea. But under collectivism the responsibility for a certain policy, project, idea, or action, is assigned to the group, to society, and thus to no one at all. Since, when Howard Roark and Henry Cameron design buildings, the public knows who created these structures, who was responsible for the undertaking, and who will answer for the design. But when collectivists, like Toohey, undertake a certain project (in a group setting) or propound certain ideas (in a collectivized atmosphere) they so disburse responsibility that no one can be identified with it.

Further, my 3rd essay claims that non-conformists, like Louis Cook, are not individualists, as thought, but rather are collectivists, in spirit. Since, the starting point on which they form their identities is the values of society. To reject them. For in the microcosm of The Fountainhead’s literary universe, which corresponds to the macrocosm of the real world, Lois Cook is a Dadaist (or absurdist) writer in the style of a James Joyce, or a Gertrude Stein. Because, like these experimental novelists, Cook also composes her books in a word salad. In an “unintelligible writing style [that] is a deliberate assault on the rules of grammar and meaning” (Bernstein). In fact, a real-life example of a Louis Cook type of non-conformist, according to Gurgen’s essay, is Lady Gaga. A name that purposefully rhymes with Dada. Since, just like Cook is a ludicrous popular artist who postures for others by writing outrageous books, Lady Gaga also poses for the crowd by performing various musical larks to amuse the masses. Then, by collecting an admission-fee for her stunts. For instance, she wore a “meat dress” to the 2010 MTV Music Awards, to display her rebellion against America’s fashion values. Given this, and other, of Lady Gaga’s actions, it can be reasoned that she is not a freethinking individual who does her own thing regardless of what the popular thing to do is. Rather, she is a posturing non-conformist a la Louis Cook, who makes a gross spectacle of herself. So, she can cash-in on the hubbub that she stirs.

Lastly, my third essay analyzes how Rand regards altruism not to be a benevolent doctrine of kindness and goodwill. But rather that altruism is a vicious doctrine that purges people of their best qualities. Since, after Catherine renounces all of her personal values in exchange for her uncle’s altruistic philosophy—like her education, her prospective marriage, and her ambition—she becomes an empty shell inside. Since, she has been trained by her uncle Ellsworth (else-worth) to believe that “unhappiness comes from selfishness.” Because after having been taught selflessness for many years, “Catherine begins to give up her sense of idealism, and the resulting decline is noticeable.” (Bayer). Earlier in the story, when she still has values—like her love for Peter Keating, for example, or her desire to go to college, for instance—Catherine looks seventeen, even though she was almost twenty. Later, “after years of social work and Toohey,” we are told that at twenty-six Catherine looked like a woman trying to hide the fact of being over thirty (Bayer). Evidently, by engaging in social work—first as a day nursery attendant at the Clifford Settlement House, then as the Social Director for the Children’s Occupational Therapy Unit at the Stoddard Home, followed by a minor bureaucratic post in Washington D.C. Catherine is no longer the starry-eyed idealist that she once was. Especially, after Catherine sorts Toohey’s mail, over many decades, files Toohey’s press clippings, over many years, answers his fan letters, constantly, and makes his scrapbook, all-the-time. Thereby absorbing her uncle’s altruistic philosophy over a long time. Not just consciously or explicitly—by asking him advice and listening to his speeches—but also subconsciously and implicitly—by reading his materials, writing his fans, and typing his speeches.

In conclusion, Gurgen’s book shows readers how Catherine’s self-sacrificial life is a cautionary tale. Because “after she surrenders every personal value,” such as her love of Peter Keating, her desire to attend university, and her ambitions for a good job, Catherine “subsists in a hollow state, an empty, bitter husk, which had once contained a vibrantly innocent soul” (Bernstein). Since, she gave up her life “to serve her uncle, Ellsworth Toohey, and join his humanitarian cause” (Bernstein). Due to which, she leads an empty, unfilled, miserable existence, since Catherine surrendered all her values to make her uncle happy.

It is in this way, then, that Ayn Rand dissolves the associative link between altruism-and-virtue. By showing readers that people who sacrifice their values to make others happy, destroy themselves. For Ayn Rand suggests, through Catherine’s dire warning, that being moral consists in being yourself, not in sacrificing everything unique about you to a community.

Don Quixote Explained:

The Story of an Unconventional Hero 2nd edition (85, 574 words)

Page Count: 348

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: 05/11/2015

ISBN #’s

- ISBN: 978-1-4817-0096-2 (Soft Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-4817-0095-5 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: $23.95 (Soft Cover); $3.99 E-Book

Press Release:

Purchase Links

Synopsis:

Don Quixote Explained focuses on seven topics: how Sancho Panza refines into a good governor through a series of jokes that turn earnest; how Cervantes satirizes religious extremism in Don Quixote by taking aim at the Holy Roman Catholic Church; how Don Quixote & Sancho Panza check-and-balance one another’s excesses by having opposite identities; how Cervantes idealizes truth-speaking women by transforming a simple farm girl named Aldonza Lorenza (who is his neighbor) into an exulted princess named Dulcinea Del Toboso; how Don Quixote tries to reform criminal characters, such as Roque Guinart, Gines de Pasamonte, and Juan Palomeque, by encouraging them to give-up a criminal lifestyle; how Cervantes establishes a religious dialogue in Don Quixote between Christians and Muslims, by creating a Muslim philosopher1, on the one hand, who steps in and out of the tale to comment on the story’s Christian translator, and a Christian translator, on the other hand, who continually comments on the identity, make-up, and practices, of the original Arab author . Other topics Gurgen’s book examines include: pre-marital love making (whether it is honorable or shameful); if countrywide expulsions of people (the Moriscos) for believing in Islam is justified; and, lastly, how religious symbols, such as a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary, is knocked down by Don Quixote, to show his disgust for the Spanish Inquisition.

1Don Quixote features a fictitious Muslim author (Cide Hamete El Benengeli) and a hypothetical Christian translator (a Morisco himself). Together they discuss original sin; religious mysticism; self-flagellation; book-burning; freedom-of-belief; freedom-of-speech; a religious shame culture; a pagan honor culture; the inquisition’s symbols of condemnation and shame (dunce caps, flamed capes, and masks-of-shame); dubious religious miracle cures, like the Balsam of Fierbras, which makes Don Quixote violently ill—instead of curing him.

Don Quixote Explained Reference Guide

(161, 917 words)

Page Count: 576

Publisher: Authorhouse

Publication Date: 06/16/2014

ISBN’s #’s:

- ISBN: 978-1-4918-7372-4 (Hard Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-4918-7373-1 (Soft Cover)

- ISBN: 978-1-4918-7371-7 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Criticism

Price: $35.99 (Hard Cover); $26.95 (Soft Cover); $3.99 (E-Book)

Purchase Links

Synopsis:

Organizes, condenses, and references Don Quixote’s 110 characters, 78 poems, 17 letters, 12 groups of people, and 19 main themes. Also, analyzes Don Quixote’s interpersonal relationships, tangible objects, bawdy jokes, Latin phrases, action episodes, and more.